Artwork by William Saroyan

“Long before Jackson Pollock, for instance, had begun his magnificent experiments and made his magnificent achievements in painting, I had already been there, I had already made the experiments and had beheld the achievements. I hadn’t made anything of them because writing was my life, and, if I may say so, my business. The drawings and paintings were part of my writing, partly of my finding out about writing, and about how I would live my life and write my writing.”

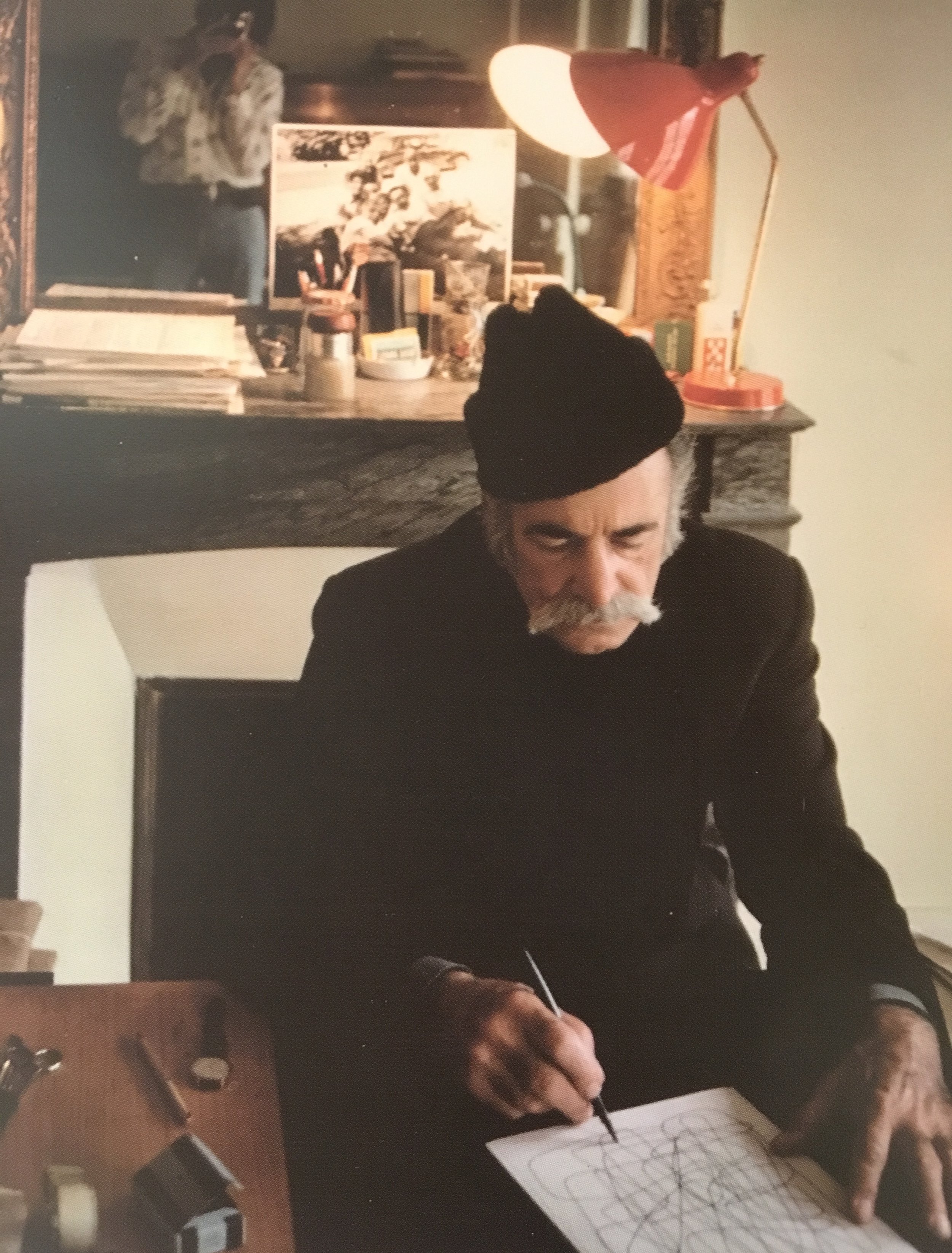

William Saroyan was an accomplished visual artist, who created hundreds of drawings and paintings during his lifetime. This section is devoted to an examination and critical review of Saroyan’s work in this medium.

The Saroyan Foundation is offering a limited number of these superior examples of Saroyan’s work for sale.

For purchase inquiries, please email info@williamsaroyanfoundation.org

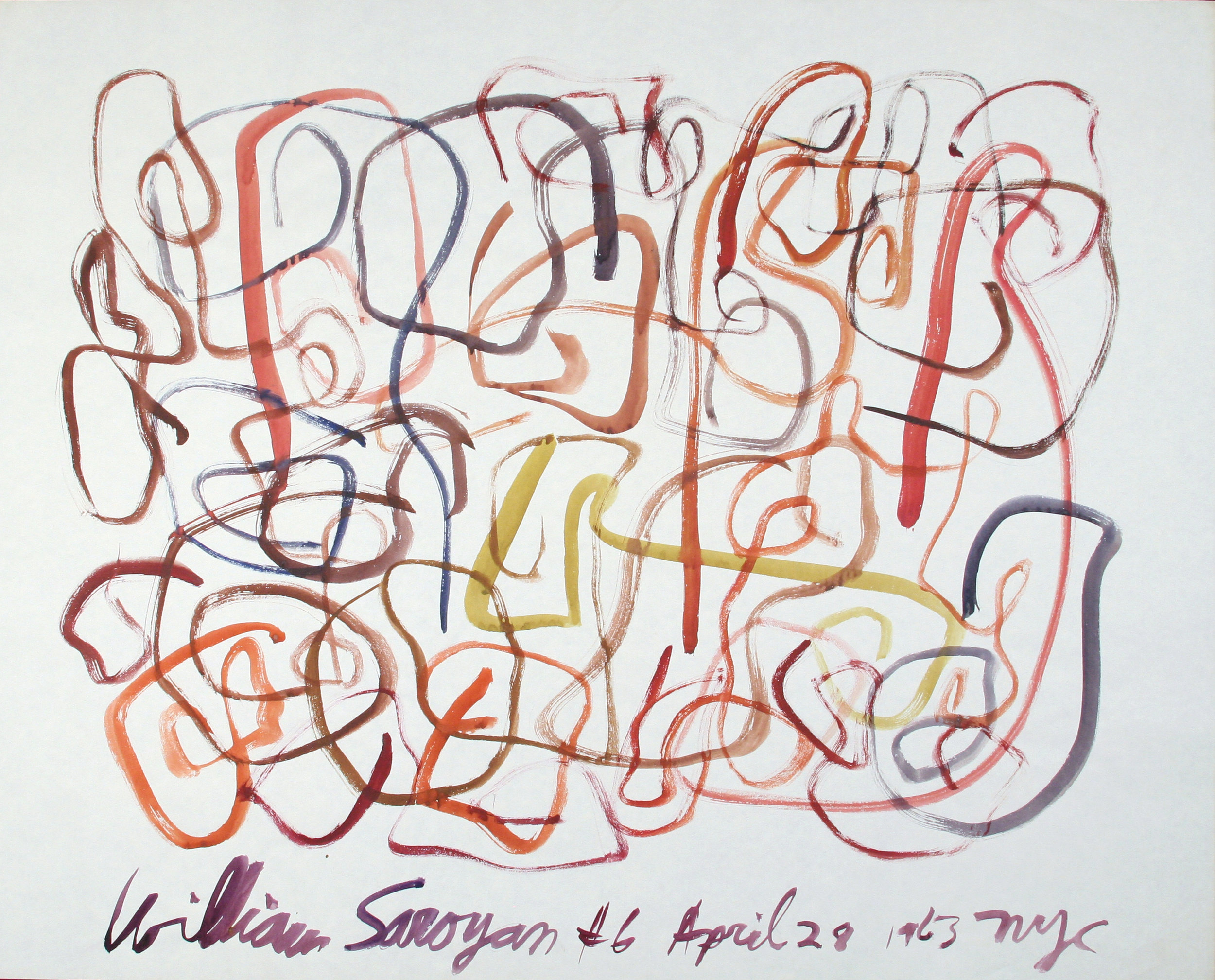

William Saroyan #6 April 28 1963 NYC

27.25" x 34"

Watercolor on paper

$14,000

William Saroyan #5 April 28 1963 NYC

27.25" x 34"

Watercolor on paper

$14,000

WS Dec 27 1965 SF

8" x 11"

Watercolor on paper

$4,500

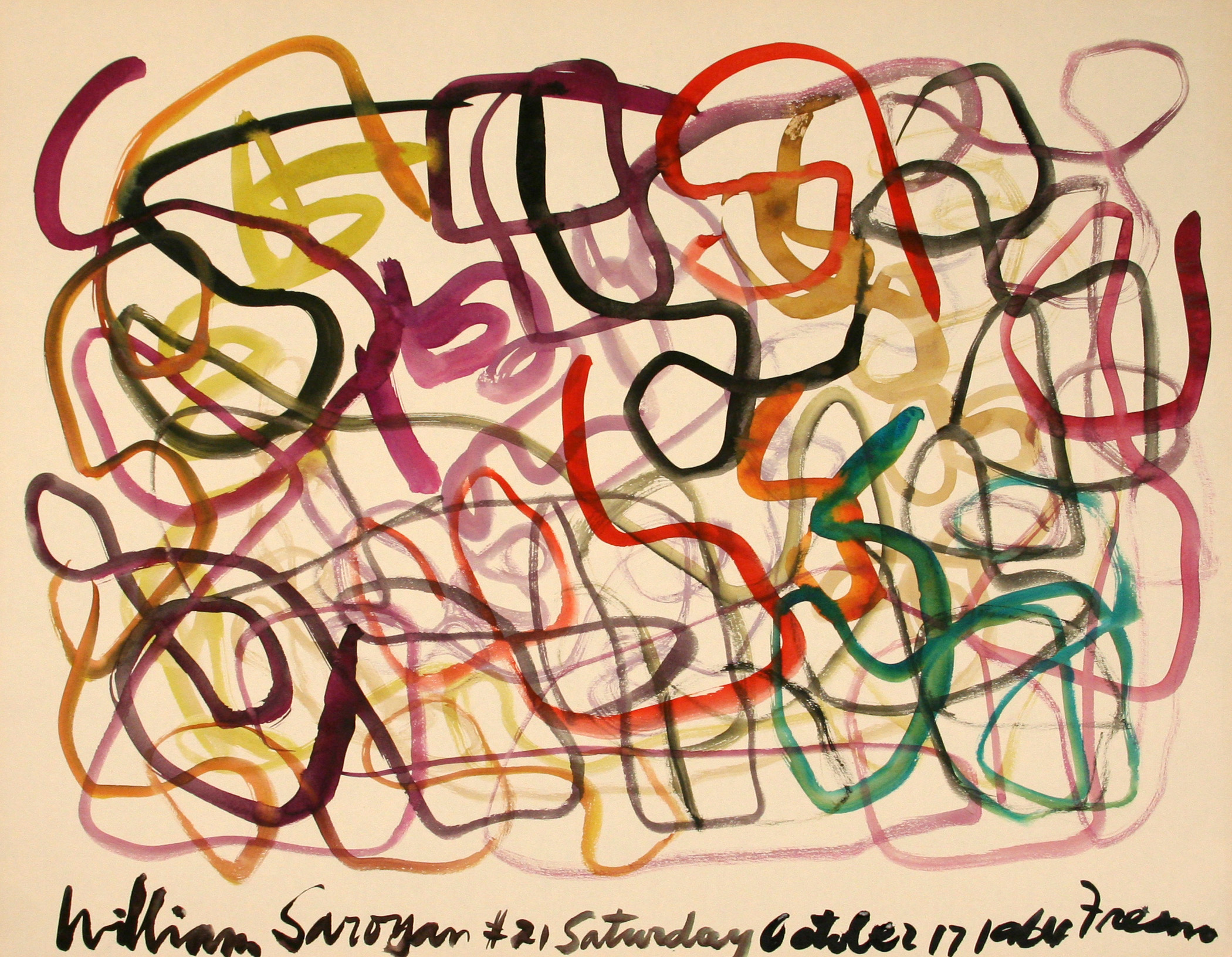

William Saroyan #21 Saturday October 17,1964 Fresno

17.5" x 22.5"

Watercolor on paper

SOLD

William Saroyan Fresno Friday, November 10, 1972 #9

8" x 11"

Watercolor on paper

$4,500

William Saroyan Fresno Tuesday October 3 1972 11 PM #1

10" x 16"

Watercolor on paper

$6,500

William Saroyan #4 March 29 1963 NYC

18.5" x 24"

Watercolor on paper

$9,200

William Saroyan #10 March 18 1963 NYC

24" x 18.5"

Watercolor on paper

$11,000

WS 11 12 70 NYC #1

10.25" x 7.25"

Watercolor on paper

$4,000

William Saroyan #3 March 10 1963 NY

24" x 18.5"

Watercolor on paper

SOLD

I Knew I Wasn’t

A Critical Art Review by Quinn Gomez-Heitzeberg

What I liked about my drawings (and paintings-on typing paper, wrapping paper, or on old newspapers) was the fact that I was sure that anybody who happened to see them would believe I was crazy. The reason this pleased me is that I knew I wasn’t.

I was especially concerned about noticing carefully people who did things like draw or paint, for it seemed to me that they were using a language which I was not sure wasn’t better than the language of words.

While writing was clearly William Saroyan’s most effective and accomplished form of expression, the sheer quantity of his paintings and drawings make them a significant portion of his creative output. Saroyan never considered abandoning the written word for painting; rather he believed that the two acts functioned together. In 1964 he would write, “The drawings and paintings were part of my writing, part of my finding out about writing, and about how I would live my life and write my writing.”

The influence of geometry is clear in his early works, which hold to straight lines and precise curves. By this time, Cubism and Russian Constructivism were well known movements that highlighted the importance of geometry in art. For a young artist wishing to be engaged with the avant-garde, geometry would have been a logical route to explore. Even in Saroyan’s early works we find an emphasis on line and repeated forms. He also demonstrated an early interest in paper as his chosen medium, completing several series on telegraph and radiogram forms.

In a second period, spanning the 1960s and 70s, Saroyan’s lines broke free of the geometric structures he had imposed upon them in the 1930s. The influence of Abstract Expressionism, the focus on gesture and line to communicate the artist’s internal feelings and conflicts, is unmistakable.

Saroyan mentions the work of Jackson Pollock several times in his writings, however, he claimed that the advancements made by Pollock had been discovered by him many years before. The surrealist method of automatic writing must also have found some connection with the calligraphic impulse inherent in Saroyan’s work. Automatism was the attempt to work without reference to the conscious mind, therefore expressing the fundamental structures of the psyche. While some of his pieces were no doubt intended to evoke a particular image or impression, for the most part they seem to be the result of the artist allowing his unconscious impulses to direct his brush.

For William Saroyan, the necessity of the creative impulse ruled his artistic life. He had to write, had to paint, had to put his hand to paper and commit his ideas. Painting became an alternate outlet for his creative energies. It was no coincidence that Saroyan’s artistic technique would have so much to do with the act of writing. Although he only occasionally went so far as to actually incorporate words into his compositions, there is a deeper connection with writing which allows us to equate the movement of his brush with the act of forming words on paper.

At times it seems as though Saroyan was struck by an idea which forced him to commit a painting or drawing to paper. Many of the pieces to which he gave titles seem to be based on offhand remarks or isolated sentences which held a fascination for him that could only be expressed in visual form. His precise recording of the places, times and dates of almost all his paintings betrays his need for order and regularity in his life. This impulse is also reflected in Saroyan’s journals, which meticulously recorded the minutiae of his daily existence.

Saroyan wrote several lines on his love of paper; especially paper which showed the marks of human use. He spoke of the practicality and availability of hotel stationery and of the intrinsic artfulness of discarded scraps of writing. Paper was seen by Saroyan as a record of human intention, a way of preserving even the most minute experience of posterity. When he died, Saroyan left behind two side-by-side Fresno houses full of objects, papers, and mementos collected over a lifetime. It is likely that he never threw out a painting or drawing. Each was filed in its proper place, a record of a given moment in his life. They were put away so that they could be taken out again and experienced with fresh eyes at some later date.

Although he considered his art to be primarily a form of personal expression, Saroyan never stopped hoping that his work would eventually reach beyond himself. In October of 1973 he wrote, “The good painting from yesterday pleases me every time I see it and I look forward later on to the doing of another, and perhaps two others, and to hope that one will be a work of genius.”

As far back as the 1930s, Saroyan had been looking at the question of artistic genius and the possibilities for his own work. His engagement with questions about the fundamental nature of art is evidenced in a sketchbook that he filled with forty-four watercolors and an essay detailing his feelings on the worth of his paintings. “The paintings in this book presented to the general public (which probably includes no more than four people, counting myself twice, once before breakfast and once after supper) in the hope that innumerable others with much more talent will be encouraged to attempt work of a similar sort, and ultimately to bring about a mild and bloodless revolution in the arts, which is always pleasant.”

If Saroyan was to conclude in the 1930s that he, and for that matter anyone could produce great art, then by the 1970s he had become more realistic about the ultimate fate of his paintings. “I must now go…and pick up and sort the paintings and stash them: that’s how it goes: do them: put them away and years later look at them again and be astonished by them.” Saroyan wrote in October of 1973. Both Saroyan’s pragmatism and optimism about his art can be traced to the realities of his personal and professional life.

The dichotomy present in Saroyan’s attitude toward his own art spring from a similar division in his life, between the realities of existence and ever present possibility of great success. Recognition for his artistic accomplishments was tempered throughout his life by the realities of his financial difficulties. The fact that Saroyan saw his art both as an entirely personal form of expression as well as works of great importance comes as no surprise.

Quinn Gomez-Heitzeberg

February 2002

Saroyan on Paper: Drawings, Watercolors and Words

The artwork of William Saroyan can be found in public and private collections across the world, a selection of which can be found below:

Armenian Dramatic Arts Alliance, Los Angeles, CA

Asheville Art Museum, Ashville, NC

Bakersfield Art Museum, Bakersfield, CA

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL

Museum of Fine Art, Boston, MA

California State University of Fresno, CA

Claremont University Consortium, Claremont, CA

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA

Fisher Gallery at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Frances L. Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY

Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA

Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art of Minneapolis, MN

Fresno Art Museum, Fresno, CA

Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, Athens, GA

St. Mary’s College Museum of Art, Morage, CA

La Salle University Art Museum, Philadelphia, PA

Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA

Museum of Art at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Museum of Fine Arts at Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL

Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, CA

Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery at Scripps College, Claremont, CA

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA

Snite Museum of Art at Notre Dame University, Notre Dame, IN

Trout Gallery at Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA